Mahima Mukherjee’s 4-year-old niece had her heart set on dressing up as the Hulk for her school’s Halloween party. “She managed to throw a tantrum and resist her mother’s efforts to dress her up as a mermaid,” Mukherjee recalled. “But when she showed up at school in her Hulk costume, she was laughed at. She was confused and upset for the entire week.”

Girls’ and boys’ clothing are starkly different, in all aspects, and often enforce a social script before children can grasp the seriousness of it.

The conversation around children's clothing has been restricted to pink vs blue, but there’s so much more to it. Right after birth, images, texts, colours, and functions of clothing determine different roles, ambitions and interests for children. The jibes at a four-year-old dressed as Hulk reveal the depth of ingrained gender stereotypes that children absorb from an early age.

HerZindagi studies the prevalence of symbolism, sexualisation, and designs of children’s clothing, to try and decode the strong differences between them – and how they shape children's perceptions growing up.

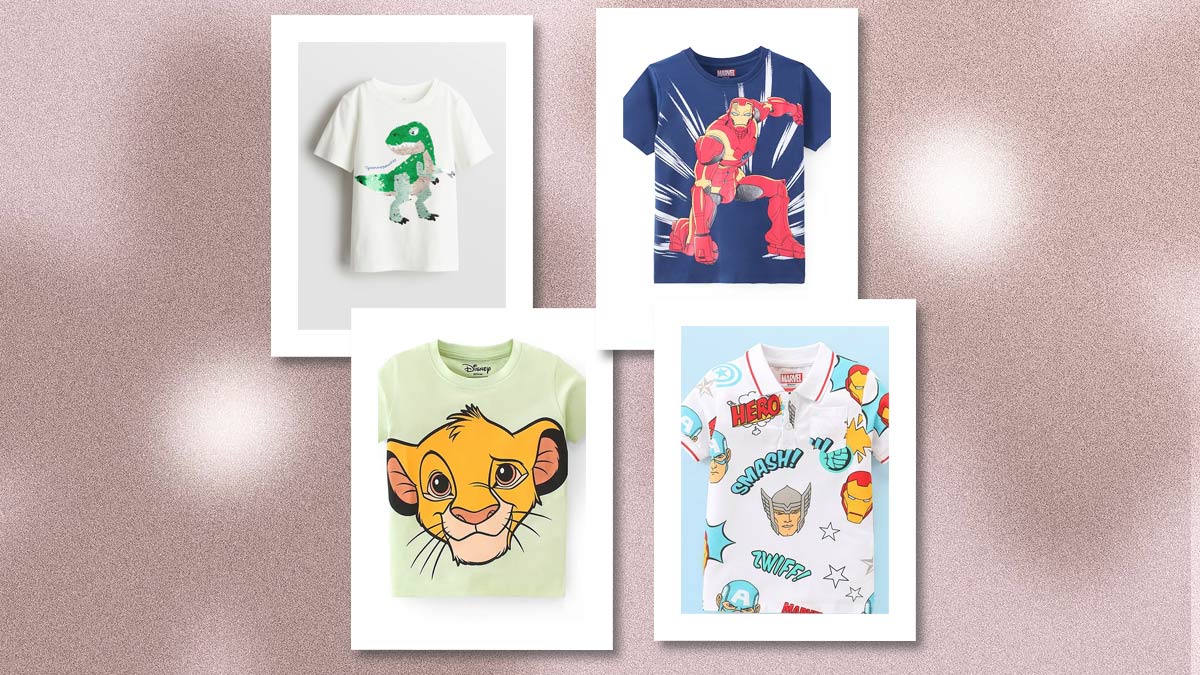

Browsing multiple children’s clothing sites shows differences in the imagery, colours, texts, and general aesthetics. Minnie Mouse, flowers, unicorns, butterflies, and hearts were common on girl’s t-shirts. Whereas, superheroes, Simba, ships, dinosaurs, and aeroplanes were prevalent on boys’ t-shirts.

When it came to text, ‘champion’, ‘hakuna matata’, ‘just have fun’ were some of the texts we saw on boys’ clothing. Girls’ t-shirts said ‘more bows, less drama’, ‘glitter, sparkle and shine’, and ‘unicorn magic’ among others.

Blue, black, and darker shades were the most common on boys' clothing while pastels and pinks dominated the girl's section.

Kristie Beaven, on a popular podcast ‘Happy Mum, Happy Baby’, pointed out that, “What you'll see on boys' clothes is predators, and what you'll see on girls' clothes is prey!" – Astutely referring to the rabbits and lamas on girl clothing vs sharks and dinosaurs on the boys.

Marianne Cronin, who did her PhD from the University of Birmingham, researched to find that 11% of boys’ clothing she sampled in the UK, had dinosaur references. She highlighted that dinosaurs rarely appeared on girls’ clothing, and even when they did, were pink in colour and adorned in sequins.

Everything on the girl's t-shirts reflected societal expectations of girls being nurturing, gentle, and affectionate. The images were soft and pleasing, and the texts were delicate.

The boy's clothing on the other hand reflected strength, dominance, and aggression. They were more action-oriented and linked to traits like bravery and leadership.

Anusua Chatterjee, a graphic visualiser who has worked extensively with a children’s clothing brand, blamed the parents’ mindset for the clothing designs. “Right from when the child is born before they even wear proper clothes, they are exposed to gendered messaging. ‘Daddy’s little princess’ or phrases like that are common. Toys, princess movies, and Barbies are given to girls. Children get inspired and want to dress up as their favourite characters. Boys watch more of ‘Bob The Builder’ or ‘Thomas The Train’ or superhero movies, leading to them preferring those designs, which are more masculine,” she said while speaking to HerZindagi.

Parenting styles shape the clothes the children end up wearing, Anusua says, “Even while children these days have strong opinions about what they want to wear, they still want to wear things reflecting idolised fictional characters or stories they’ve been most exposed to.”

Beyond colours and graphics, children’s clothing reveals gendered expectations. Girls’ clothing often prioritises aesthetics over function. Dresses with lacy skirts, tops with frills and ruffles, and shoes with glittery decorations are common for young girls. While these items may be cute, they can be impractical for active play.

“The emphasis on aesthetics in girls’ clothing—such as frills, tight fits, and delicate fabrics—compared to the practicality of boys’ clothing, with functional designs like larger pockets, durable fabrics, and looser cuts, suggests that girls are encouraged to prioritise appearance over function from a young age, while boys are expected to be more active and free to explore their surroundings,” highlighted Mahima, a feminist historian currently pursuing her second Masters from the University of Toronto.-1730206522970.jpg)

A dress with tight waistbands, decorative elements, uncomfortable necklines, and stiff fabrics is likely to discourage a girl from physical activities and playtime that require a wide range of movement

She highlighted how many schools still require skirts for girls as part of the uniform. “Schools often expect girls to wear an extra layer of shorts for physical activity, instead of offering pants or joggers as options,” she explained. Mahima recalled how in her school, girls were told it was ‘unladylike’ and ‘ill-mannered’ to sit without crossing their legs, reinforcing ideals of feminine behaviour based on clothing.

The emphasis on style over function subtly enforces the stereotype that girls are meant to be admired, not necessarily active participants in rough-and-tumble activities.

Boys’ clothing, on the other hand, is often designed for functionality and movement. Cargo pants with multiple pockets, sturdy jackets, and loose-fitting t-shirts are common. These clothes allow for a greater range of motion and are likely to be more durable. It reinforces the idea that boys are expected to be physically active, enjoy sports, and be adventurous.

“My nephew visited me last week, and at a point, he tried sneaking off to play video games. He even managed to fit his father’s phone into his pants pockets. I’ve never had the luxury of doing that. Why do a 7-year-old boy’s pants have bigger pockets than mine? The patriarchal gender imagery that men’s clothing needs to be more functional, ‘active’ and practical, as opposed to the ‘passive’ designs of bows, ruffles and feathers for girls, is normalised from such a tender age that children are conditioned into thinking that that is how it should be,” highlighted Mahima.

Clothing for young girls has steadily grown to mimic those of women, with an extra focus on sexualisation. Halter necks, crop tops, string tops, deep necks, sheer stockings, hot pants, and mini skirts can be easily found in the racks of girls' clothing

Mahima, with two nieces under the age of five, has witnessed this issue firsthand. “Recently, I was looking for princess dresses for my nieces (they have been watching the Disney animated movies on repeat) and I found costumes for 2-3-year-old girls with hip-enhancing corsets. Why does a 3-year-old’s princess costume have that? I cannot even begin to unpack the patriarchal mechanism at play. Are you trying to depict a three-year-old girl as sexually desirable and suitable for childbearing?,” she questioned.

Apart from the clothing itself, brands have even started formulating full make-up ranges for children including lip and cheek tints, eyeshadow palettes, concealers, and more. Asking a 4-6 year old to ‘conceal’ facial irregularities is likely to do more harm than good. These add to a child’s wardrobe, further egging her on to conform to societal beauty standards.

The traditional notions of strong masculinity for boys vs sweet femininity for girls are reflected in clothing for children, right from a tender age. The stark contrast in design, colour, and symbolism between clothes marketed for boys and girls often subtly and sometimes overtly teaches children what behaviours, interests, and roles are ‘appropriate’ for their gender.

Mahima highlights how clothing marketed toward young girls can blur the lines between childhood innocence and adult standards of beauty and desirability. “Designs like halter necks, bikinis, crop tops, corsets, lace-backed tops— all of these normalise the sexualisation of girls. When we establish a certain kind of appearance as the mainstream or status quo, it makes it easier to label individual expressions of identity as ‘deviant,’” Mukherjee added.

Her critique is rooted in her background in feminist studies, where she has examined how clothing acts as a medium through which patriarchal gender binaries are perpetuated. “Clothing is a powerful tool for reinforcing what is considered ‘ideal’ masculinity and femininity, especially in the context of consumer culture," she explained.

Body image issues, self-objectification, and the internalisation of gender norms happen when young girls are dressed up, or encouraged to act like adult women. These designs reinforce gender stereotypes and promote problematic ideals of femininity that children are too young to understand or consent to.

Shirts for girls didn’t even exist as a category on most sites. Some tops with bows looked and functioned like shirts, but were adorned with flowers or polka dots.

This discrimination creates barriers in girls’ minds early on. “Not only do they reinforce gender norms but also limit girls’ ability to explore their physical capabilities and the world around them, shaping their sense of what is appropriate behaviour or interest for their gender. Moreover, it generates anxiety by keeping them acutely aware of their bodies in social spaces along the lines of ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ appearances. This early conditioning negatively impacts confidence, self-expression, and the roles they see themselves fulfilling,” added Mahima.

Mahima highlighted how that hampers a child’s development of personality. “This kind of primary conditioning can restrict a child’s sense of agency in exploring their preferences and desires, which eventually causes conflicts in the development of an independent and unique identity. It creates a pressure to conform to an invisible social-moral code that determines a person’s membership and acceptance in heteronormative society according to how they dress and behave,” she stated.

Given the extent to which clothing lines across brands are restrictive and similar for children, it’s unlikely that parents trying to give their children more choice or agency will have a range of options.

Also watch this video

Herzindagi video

Our aim is to provide accurate, safe and expert verified information through our articles and social media handles. The remedies, advice and tips mentioned here are for general information only. Please consult your expert before trying any kind of health, beauty, life hacks or astrology related tips. For any feedback or complaint, contact us at [email protected].