Sacredness, Sin or Shamefulness

When a random group of women were surveyed, 59% of women answered that they’d felt conscious about their breasts, and around 60% of them said that they’d received judgement, stares or advice on their breasts.

When they were asked what part of one’s body women feel most uncomfortable about when stared at, 65% answered breasts.

HerZindagi conducted a survey of over 50 women, on their relationship with breasts, only to find layered, complex answers that led us to digging deeper.

Have you ever been concious about your breasts/clevage

Have you recieved judgement/stares/advice on

Throughout history and in present times, breasts have been a deeply contested aspect of women’s bodies in India, shaped by cultural, societal, and media narratives.

They are among the most sexualised, scrutinised, and controversial parts of the female body, often subjected to objectification, censorship, and shame. Women have even fought caste-based struggles over the right to cover their breasts. Ideas of modesty and clothing have been debated and have evolved in many ways over time. The media, meanwhile, both objectify breasts and dictate the standards for what is considered attractive. The presence of unwarranted gazes, harassment, and misogyny around breasts has only added on.

Whether through historical, social, or personal battles, HerZindagi speaks to stakeholders and women on why the topic of breasts remains a source of tension for women. This struggle for most, takes many forms—sometimes it’s in the form of an internal conflict, as women wrestle with self-image and societal expectations, and other times it’s an external fight against the outer world – dominated by patriarchal ideas of beauty and the male gaze. In every context, the female experience around breasts reflects a broader war over autonomy, dignity, and identity.

Caste Wars Fought Over Breasts

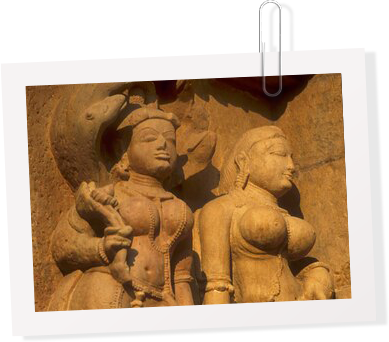

Covering breasts was not a norm throughout Indian history.

One of the most prominent glimpses into the Indus Valley Civilization is the sculpture of the dancing girl. It is almost symbolic of the prehistoric civilization and shows a nude woman with stylized ornamental jewellery, including stacked bangles.

Erotic motifs depicting nudity are immortalized in stone on the lower walls of the 13th-century Sun Temple at Konark in Odisha. Nudity is a prominent feature in the paintings and sculptures found in Maharashtra's Buddhist rock-cut caves at Ajanta and Ellora, and in Khajuraho.

Manisha Gawde, an art curator, art columnist and artist explains, “As civilization developed, a larger population ensured more security and power. To promote reproduction, sculptures depicted nudity and intimacy, serving as reminders of divine orders to procreate.” She adds that in earlier times, clothing was primarily for protection from the cold, with no moral judgment attached to nudity.

Manisha

Over time, societal thoughts around breasts changed. When the British invaded India, they brought with them a new set of ideas around modesty and morals, and thereon, women started covering their torsos.

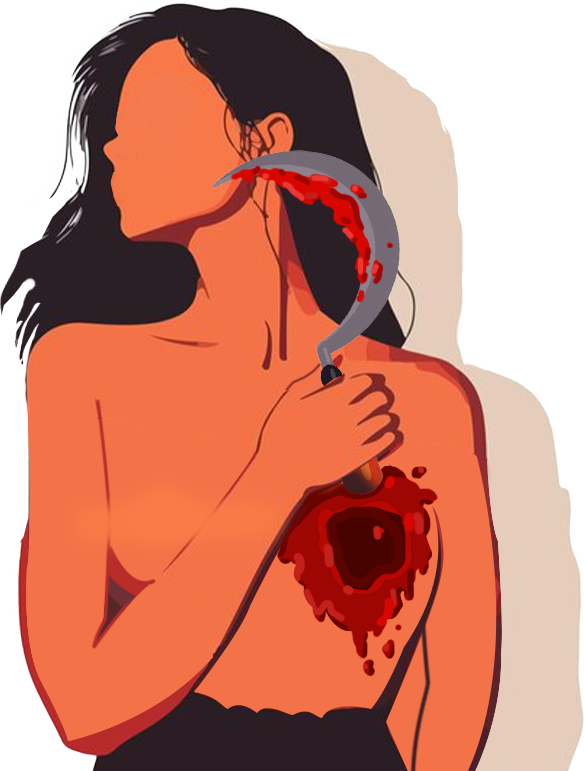

Nangeli: The Woman Who Rebelled Against the Breast Tax by Chopping Off Her Breasts

In most southern states, women remained bare-chested in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Kingdom of Travancore, which is now part of Kerala, imposed a poll tax on lower-caste women who covered their breasts in public.

Mahima Mukherjee, a feminist historian explains the plight of Nangeli, widely known for opposing the breast tax. “Nangeli was a woman who belonged to the Ezhava caste in the 19th Century, an oppressed caste community who had to pay the ‘breast tax’ if its women covered their breasts (covering of breasts was made into a privilege available only to upper-caste women),” she said

Tax inspectors were appointed to collect the tax and ensure that no one broke this law. Nangeli refused to comply, cut off her breasts in protest, and succumbed to the excessive blood loss. Her husband died by suicide, by jumping into her funeral pyre.

“This is just one of the many histories of caste violence that upper-caste people have been complicit in removing from public memory to enforce historical amnesia about caste. Breasts in general have historically been a site of violence, sexualisation and patriarchal control,” highlighted Mahima.

The village of Mulachhipuram, which literally translates to "land of the woman with breasts", was named in honour of Nangeli.

She added, “In this particular example, the breast tax highlights the multiple oppression that women of oppressed castes have been historically exposed to. It challenges the homogenisation of the category of ‘women’ that exists in feminist narratives, which generalises the lived experiences of oppression of all Indian women by invisibilising the differential experiences based on caste.”

Breasts in this scenario were entrenched as sites of caste-based oppression.

Religion: The Paradox Between the Divine Feminine and Profanity

In several parts of India, breasts are worshipped as a symbol of the feminine divine, especially in Hindu traditions.

The Mangla Gauri temple in Shakti Peetham, Gaya, Bihar worships Sati in the form of breasts, seen as a symbol of nourishment. It is believed that Goddess Sati’s breast fell here.

While breasts are worshipped in one part of the nation, there’s a paradox at play.

Women aren’t allowed to enter certain temples in India, like the Sabarimala temple. The defending logic was that Lord Ayappa in Sabarimala, was celibate, and thus women of reproductive ages shouldn’t enter the temple. In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the temple's practice of excluding women was unconstitutional by a 4:1 majority.

In South India, marriage traditions include the bride wearing a pendant symbolizing breasts, signifying fertility and motherhood. Yet, on the other hand, women breastfeeding in public often face criticism – with such a natural act being viewed as shameful. On a more perverted note, the dark sides of the internet even have pages with thousands of followers, which solely post videos of breastfeeding mothers. Comments on them are mostly on the lines of deriving sexual pleasure.

In March 2018, a south Indian magazine, Grihalakshmi, featured model, poet and actor Gilu Joseph on the cover, while breastfeeding. It came with the headline

“Mums tell Kerala: don’t stare - we need to breastfeed”

It sparked widespread outrage, with many calling it ‘inappropriate’.

This paradox is prominent and profound in a society where breasts have historically been symbols of divinity, strength, and sustenance. In temples and rituals, they are celebrated as sacred—embodying life and maternal power. Yet, the same cultural and social lens also happens to impose notions of shame and sexualization on breasts, forcing women to navigate a complex web that oscillates between reverence and objectification.

Sexualisation: Media, Movies and Feminism

Films, shows and general pop culture depictions of breasts have often shaped a lot of public perception of them.

The hyperfocus in Bollywood on breasts—through suggestive outfits, camera angles that zoom in on cleavage, and provocative dance sequences—has contributed to a narrative that views the female body as a spectacle rather than a person’s own.

Actress Chhavi Mittal highlights, the entertainment industry’s primary goal is to capture attention and drive high TRP ratings. She said, “They show what attracts the most attention. There is nothing wrong with this. Artists who want to do this are often trolled, which is wrong because every woman should have the freedom to make decisions about her body without any social pressure and stigma.” She also highlights the paradox: while women should have the autonomy to express themselves as they choose, the societal backlash they often face points to deeply entrenched double standards.

CHHAVI

How Bollywood portrays women’s cleavage has evolved through distinct archetypes, often tied to specific character tropes.

Figures such as the "other woman," femme fatales, vamps, and dancers in "item numbers" are mostly shown with emphasis on cleavage. On the other hand, roles like the nurturing mother, the sweet girl-next-door, or the virtuous love interest are rarely sexualized in this manner. This dichotomy creates a stark divide in how female characters are perceived, where showing cleavage is associated with negativity, seduction or sexuality.

It’s not uncommon to find media outlets publishing stories about actors’ ‘revealing’ clothing or cleavage. Once, a publication published a piece highlighting the cleavage of actress Deepika Padukone. She replied to it saying – "YES! I am a Woman. I have breasts AND a cleavage! You got a problem!!??" - which was re-tweeted more than 7,000 times.

The feminist debate around breasts adds more layers to the issue. Some say that women who play these roles are contributing to their own selves being objectified. However, others counter that with the argument that the real issue lies in denying women the agency to make their own choices, whether it’s embracing such depictions or rejecting them. This discourse points to what some call the "Kim Kardashian conundrum," where women are scrutinized for leveraging their sexuality in a way that simultaneously empowers them, but is definitely feeding into a system of commodification.

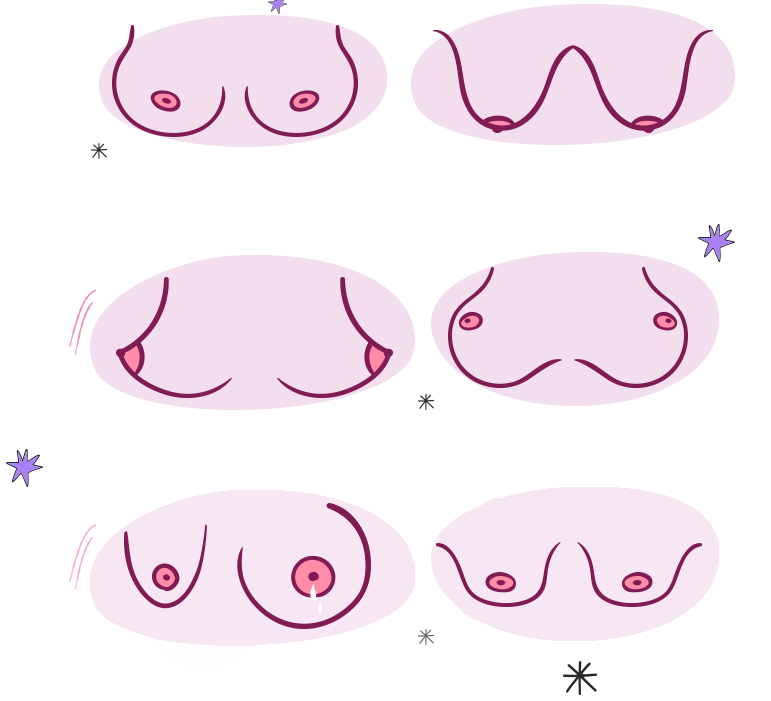

The hyperfocus on breasts in popular culture is deeply rooted in patriarchal notions of beauty, setting rigid standards for what they should or shouldn’t look like. The "ideal" is often portrayed as perky, firm, round, and free of any sagging—a narrow definition that leaves little room for individuality or natural variation.

Actress Chhavi Mittal highlights, "There has always been a special kind of pressure regarding breasts in the fashion industry. Whether it is on the covers of fashion magazines or runway shows, there has been an attempt to mould women into an ideal body shape. Women who are thin are called "flat-chested", while those whose breasts are more prominent are labelled as "curvy".

Such labelling adds insecurities to women’s minds, leading to them considering their breasts “imperfect”.

The Internal Battle: Loving the ‘Imperfections’

The portrayal of "perfect breasts" in media and society has left many women grappling with an internal struggle to embrace their bodies.

They often face conflicting emotions as they attempt to accept their breasts with what are labelled as "imperfections"—be it scars, changing shapes, stretch marks, sagging, or other natural variations.

This obsession fuels an entire industry of products designed to enforce these unrealistic norms, from minimizer bras to ultra-padded options that reshape and try to conform to set beauty expectations.

At the extreme end of this spectrum lies cosmetic surgery, with breast augmentations, lifts, and reductions marketed as solutions to help women "achieve perfection." Some reports and anecdotes suggest there’s been a 100% increase in breast reduction surgeries since 2019.

How is your relationship with your breasts?

Chhavi, the actress, believes that the size and shape of a woman's breasts matter do matter. She underwent a myriad range of emotions while undergoing treatment for breast cancer. She says, "When I was to undergo surgery, many emotions were flowing in my mind. One of these was the worry that now my breasts will not look the same as before. When I wear a dress with a deep neckline, a mark will be visible. Every woman wants to have no scars on her body, and especially the beauty of the part that makes her feel like a woman, matters a lot." These pressures underscore how societal beauty standards commodify and end up regulating women's bodies.

In this instance, women are constantly battling the preconceived notions of beauty perpetuated by capitalism and relentless marketing. Even deeply personal choices—such as opting to go braless—are considered radical, and often met with reactions of controversy and debate.

Nipples: Integral to One’s Perception of Feminity and Beauty

Nipples and breasts are deeply tied to a person’s sense of femininity and beauty. For many women, losing these body parts due to health conditions such as breast cancer can feel like losing a part of their identity. To reclaim their confidence and sense of self, some turn to unique options, like nipple tattoos, to restore what was taken away.

Mahesh Chauhan, a professional tattoo artist, specializes in creating realistic nipple tattoos for women who have undergone mastectomies or other surgeries. Sharing one of his experiences, he recalls, “A lady came to me with her husband after having her nipples removed during surgery. Before proceeding, we counsel every client thoroughly. We also offered her the option to have the tattoo done by a female staff member for her comfort. However, she declined, saying she wanted perfection and trusted me to create it.”

Mahesh has also had the experience of tattooing on transwomen.

Mahesh highlights the immense responsibility such work entails. “As an artist, it’s daunting to challenge nature and recreate something so personal and intimate. It was one of the toughest jobs I’ve done,” he says. The outcome, however, was remarkable. “When the tattoo was completed, it looked incredibly real, and the client was satisfied. Seeing her smile made it worth all the effort.”

Here, art can play an immense role in healing—not just physically but emotionally—by helping these women feel whole again.

Sin: Violence, As A Means of Exercising Power

Mahima Mukherjee, the feminist historian, while speaking to HZ, highlights how violence around breasts through history has been used as a tool for exerting dominance and power.

She explained, “During events of communal violence in India, be it the violence that ensued during Partition or the 2002 Gujarat riots, one of the most common forms of sexual violence inflicted upon women was the cutting off their breasts by members of rival communities involved in the violence. It is common knowledge that the honour of a community is located on the bodies of its women— they are the site of waging war, a battleground of sorts. Since breasts are traditionally associated with femininity and motherhood, such deliberate acts of multiplication are inflicted to dishonour the community by exercising power over female reproductive bodies through their ‘desexualisation’.”

Mukherjee further highlighted that such brutal acts of violence are not only physical assaults but also deeply symbolic. By mutilating breasts, perpetrators attempt to erase the femininity and humanity of their victims, reinforcing their dominance and inflicting generational trauma.

The prevalence of sexual violence against women remains alarmingly high, with breasts often at the centre of such attacks. Groping, for instance, is among the most common forms of harassment women endure.

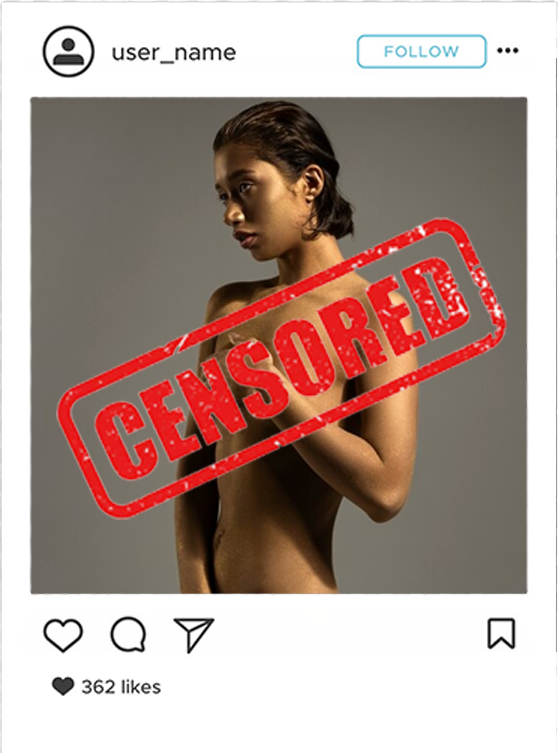

Censorship and Misogyny

The censorship of women’s breasts, especially nipples, on social media platforms highlights deep-seated gender biases. While men can post bare-chested photos without question, women are policed, shamed, or even banned for similar displays of their bodies. The dual standards, where women’s nipples are censored because they don’t conform to “community standards” of social media platforms, are a blatant display of gendered censorship. Ironically, these same platforms often allow sexualized portrayals of women’s breasts in advertisements or entertainment, showcasing a hypocritical double standard.

As described earlier, cinema’s portrayals often have far-reaching impacts. Violence and misogyny are often intertwined with such depictions, creating narratives that fetishise dominance. These portrayals not only titillate audiences but also perpetuate dangerous stereotypes, potentially fueling unhealthy attitudes toward women. Such representations have often been linked to the desperation and even driving India’s pervasive rape culture.

Amid this external misogyny, women are caught in a constant internal paradox. They navigate a world that tells them their safety is their responsibility—whether by covering themselves with scarves to keep predatory glances at bay or by adhering to societal norms of “modesty.” Yet, they also grapple with the truth that no amount of clothing can ever truly be seen as “protection” from harassment or assault. Neither does any kind of clothing be “asking for it” when it comes to sexual harassment. The burden of navigating this double-edged reality forces women to balance between fighting back and internalizing blame, all while living in a society that refuses to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.