PUBLISHED ON May. 24, 2024

Fueled by a growing middle class, increased disposable income, and the influence of global fashion trends, India’s latest fashion has evolved and the appetite for trendy and affordable clothing has soared. Spearheaded by celebrities, influencers, and social media, looking fashionable’ has shifted towards temporary trends, not repeating outfits, and a constantly evolving wardrobe.

“Everyone follows influencers and trends, they want to upload pictures all the time, look trendy, buy clothes to only wear them once or twice and brands end up selling cheap clothes to cater to these changing trends,” said Pankti Pandey, a sustainability advocate and scientist who runs an Instagram page called ZeroWasteAdda, promoting sustainable choices, slow fashion, and slow food principles.

A report by the Indian Chamber of Commerce predicted that by 2023, each person will spend Rs 6,400 on clothing, which is a sharp rise from 3,900 in 2018.

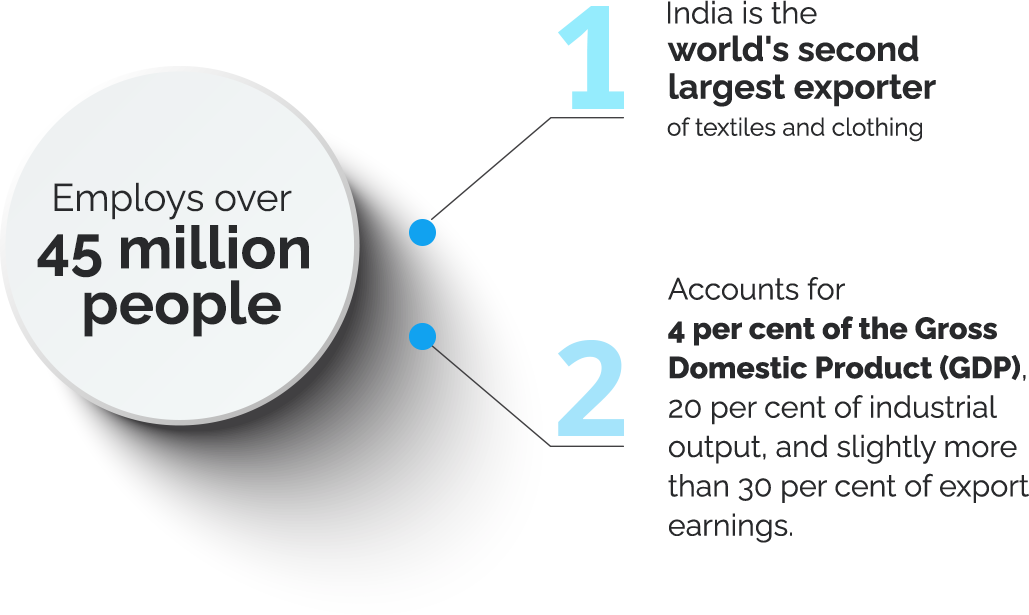

To meet this expanding demand and to also cater to international markets, India’s textile industry is huge, as evidenced by the numbers

“For a trend, fast fashion brands are generating lots of clothes,” said Pankti. The process of making these has a multi-fold negative impact on the environment. “When the clothes don’t get sold, they end up in landfills”, she added.

HerZindagi spoke to experts, activists, influencers, and brand owners, to understand the environmental impact of the fast fashion industry. In turn, we discovered its impact on customers, beyond what they might typically assume.

How Fast Fashion Came Into Vogue

Back in the day, the fashion industry used to operate primarily over two seasons - spring/summer and autumn/winter. Several months were spent pondering upon upcoming trends and just two sets of fresh styles were created by brands. However, that changed. During the 2000s, with the emergence of international fashion giants like Zara and H&M, a business model with 52 annual ‘micro seasons’ meant new collections were launched every week. This was when ‘fast fashion’ gained prominence, particularly among these brands.

It referred to the quick pace of garment production that characterised much of the fashion world, with many other brands following suit.

This trend, however, came at a great cost. Environmental damage, bad working conditions, poor wages, and huge waste amounts were the main characteristics of this trend.

The result was a vicious loop that affected all stakeholders. “Consumers are now buying with a disposable mindset, thus brands make clothes without durability in mind,” explained Shruti Singh of Fashion Revolution India. “The biggest link to why a consumer should care is that microplastics are being found in our bloodstream.”

The biggest link to why a consumer should care is that microplastics are being found in our bloodstream Shruti Singh, Country Head, Fashion Revolution India

Fashion Revolution India is the national branch of a global nonprofit movement, established in response to the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013. Rana Plaza was a garment factory that produced clothing for major fashion brands like Zara and H&M. The collapse claimed over 1,100 lives and left another 2,500 people injured, exposing the human cost of fast fashion and serving as a wake-up call for the fashion industry, imploring stakeholders to find out who’s truly paying the price for fast fashion. But to understand the impact on our individual lives, we traced the production process of a garment.

The Life Cycle of a Garment

Cotton Cultivation

- Uses land, energy, and water

- Chemicals used to grow cotton, harm the land

- Cotton uses 6% of the world’s pesticides and 16% of all insecticides

- The run-off with pesticides, fertilisers flow to rivers, eventually infiltrating our food chain

Fabric Production

- Production waste

- Dyeing releases toxic pollutants into the river

- Chemical waste generated

- Greenhouse gases emitted

Transportation

- Fibre is transported to factories

- Greenhouse gases emitted

Shipment

- Packaging waste generated

- Greenhouse gases emitted

Making of garment

- Poor labour conditions

- Unfair wages

- Greenhouse gases emitted

Owning and use

- Laundry and dry-cleaning harm the environment

Waste

- Landfills

Garment production requires a significant share of natural resources like water, energy, and raw materials.

According to UNCTAD, around 93 billion cubic metres of water - which is enough to meet the needs of five million people - is being used by the fashion industry annually. Additionally, around half a million tons of microfibre, which is equal to three million barrels of oil, is being dumped into the oceans every year.

Subsequently, the dyeing and finishing textile industry is a major water polluter across the globe.

The chemicals used in making clothes, like dyes and bleaches, are harmful to the environment.In India, the detrimental effects of the textile industry can be tangible. Here, we explain how.

Panipat

Textile recycling hub.

Home to thousands of dyeing plants and fertiliser factories, which dump their untreated effluents into drains that flow into the Yamuna river. According to a survey by CPCB, industries in Panipat were discharging the highest quantity (45%) of pollutants into the Yamuna.

Shiv Vihar, Delhi

Known as “cancer colony” thanks to the hazardous waste emitted by its jeans dyeing units. The Supreme Court ordered the closure of all polluting industries in Delhi.

Pali, Rajasthan

Bandi River is contaminated with industrial pollutants, mainly from the textile industry. Renders fertile land unsuitable for agriculture. Affects the livelihoods of multiple farmers in nearby villages.

Patwa Toli, Gaya district, Bihar

Known for colourful textiles.

Effluents being routinely disposed from dyeing, washing and pressing units. Toxic red, green, yellow water often seen making its way to the Falgu river, a tributary of Ganga. Years of this led to the groundwater being contaminated, leading to hand-pumps pumping out multicoloured water, with a stench. Local people often have to walk for an hour to collect safe drinking water.

Mumbai

River Waldhuni, which supplies water to the Mumbai Metropolitan Area, routinely runs red with dyes from textile industries. Blue dogs, afflicted by indigo dyes, have been known to roam the city’s streets.

Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu

Garment production hub for global fashion brands. Around $3.5bn worth of exports every year. Untreated wastewater from dyeing and bleaching units has transformed the Noyyal river into a toxic sewer and rendered the agricultural land around Tiruppur largely unproductive, taking away the livelihoods of thousands of farmers.

It is for these reasons, that sustainable fashion is the need of the hour.

The latest 2024 Instagram Trend Talk, which studied the results of a survey that aimed to find out Gen Z trends across the US, UK, Brazil, India, and South Korea, found that in the realm of fashion, sustainability is the key feature. Fashion trends, they say, will revolve around thrifting, vintage, heirlooms, repeating outfits, and DIY.

Case Study of A Sustainable Brand, Iro Iro

Iro Iro is a sustainable fashion brand, based out of Jaipur, that was born with the mission of reducing textile waste. They’ve showcased their work at the Lakme Fashion Week as well.

“I grew up in a garment factory. That made me very aware of the wasteful nature of the garment industry,” said Bhaavya Goenka, founder and designer at Iro Iro. “This isn’t because people working in it aren’t good, but that’s how the industry is designed.”

She explained that the post-industrial revolution industry is designed in a way that’s unkind to the planet, to the makers, and everything else in between, except the person at the top of the value chain who is accumulating wealth. “The fashion industry is kind to nobody else, and I wanted to change that,” she said.

Bhaavya’s mom used to make hangers out of waste from the industry, and she passed away from cancer while Bhaavya was still studying.

“Working with waste became a way for me to keep her alive,” said Bhaavya. “Taking the waste to the village and creating something out of it was also a way to create employment in the village.”

Iro Iro works by taking textile off-cut waste from various factories, collecting it and taking it to the village. There, the waste is sorted out in terms of weight, colour and size. It’s then converted to linear form. Workers then weave it into a new fabric after researching indigenous techniques of weaving. It’s then cut into a garment and stitched. They also do zero-waste packaging.

What sets it apart is also its minimal design aesthetic, which blends traditional Indian craftsmanship, with modern silhouettes.

“Dealing with the unkindness of the industry is the biggest challenge. And that the industry is so huge and overwhelming,” added Bhaavya.

How Your Choices Directly Impact the Environment

“Most people don’t even know that what we’re wearing is affecting the environment,” said Pankti Pandey, a sustainability advocate working towards raising awareness through social media. “People may think that their cotton top is environment-friendly, but rarely know about the water footprint or the carbon footprint behind that cotton cloth, or jeans.”

People may think that their cotton top is environment-friendly, but rarely know about the water footprint or the carbon footprint behind that cotton cloth, or jeans. Pankti Pandey, a sustainability advocate

She also emphasised how dyes affect the waterways around us, which people don’t think about when picking out a piece of clothing. If the clothes are synthetic, made from polymers, made in the factory, then again there has been increased water pollution, chemical pollution and more,” she added. “Those clothes are also non-biodegradable, so they stay in the landfills for years.”

This is where reading the label, and being curious about what materials our clothes are made of plays a big part for consumers. Shruti from Fashion Revolution highlighted, “Good questions to ask, and also two campaigns we ran, were Who Made My Clothes? And What’s in My Clothes?”

Why Should You Care?

Shruti, the policy expert says that this year has been one where we've all felt the impact of climate change. With global warming, flash floods to rising sea levels, all communities have been affected in some way or the other.

“Fashion has a strong link with climate as it contributes to 4-8 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions,” she emphasises, urging people to sit up and take note. “The present generation should care because it is the earth that they will inherit and fashion is pushing the planetary boundaries.”

Globally, estimates suggest that about 100 billion garments are produced by the fashion industry annually and every year, around 92 million tons of clothing end up in landfills. Of this, only about 20% of textiles are collected for reuse or recycling globally.

“This leads to microplastics eventually finding their way to our bloodstream, causing health issues. It has been linked to carcinogens,” highlighted Shruti.

What Can You Do?

Being responsible and conscious as consumers is the first step.

“When it comes to trends, I think it’s easy to give in because they’re available so quickly and everyone wants to participate. What we can do with those purchases is try to make the most use of them and re-wear or restyle the pieces in as many ways as possible,” said Aashna Hegde, a creator with over one million followers. “Also, consciously invest in pieces that will be ‘timeless’ and grow old with you!

Influencers themselves have a responsibility to do better and promote sustainable choices. Pankti added that awareness is lacking, and if influencers and creators of all domains can speak about the environment, it could create a significant impact.

Thrifting, or picking out second-hand clothes, is another way to ensure a longer life for a garment. Ashna runs a thrift store on Instagram, called ‘Out Of Stock’, proceeds of which go to an animal shelter.

Choosing sustainable brands is another thing people can do.

How to Know If a Brand is Sustainable

With sustainability becoming a buzzword, many brands claim to be ‘green’, but not all of them are sustainable.

“Transparency is what consumers should look for”, said Shruti, as there is no codified check-list that makes a brand sustainable. Whether it’s globally, or at national level, there is no definitive list of things brands need to fulfil, to be able to market themselves as sustainable.

She also asked how profit is distributed in the supply chain system.

A survey conducted by the Changing Markets Foundation, covering 50 of the largest global brands, revealed that nearly 60% engaged in some kind of ‘greenwashing.’ The majority lacked transparency regarding the specific factors that made their clothing truly sustainable.

Fair pay and gender parity among workers is what one can look out for, to make sure workers are treated decently. Secondly, what materials are used in the clothing and what the company is doing about waste are things consumers should be curious about. “Ethical, authentic sustainable brands would be happy to share these data points and back their claims by evidence,” added Shruti.

Slow Fashion is Fair-Priced

One of the biggest critiques of sustainable brands is that the products are ‘too expensive’. Shruti explains that the right question to ask isn’t why the products are too expensive, but why fast fashion is so cheap. “Slow fashion, in most cases, isn’t expensive. It’s fairly priced,” she said.

“If you are using good and durable materials, you're using dyes which are good for the planet, and you're making sure that waste gets disposed of properly, there is a cost attached to those. You're paying your worker fairly too,” she said while explaining how the costs of each garment produced by sustainable brands tend to go up.

If you are using good and durable materials, you're using dyes which are good for the planet, and you're making sure that waste gets disposed of properly, there is a cost attached to those. Shruti Singh, Country Head, Fashion Revolution India

But can prices become a little more affordable? “I think so, yes, but then again, that will happen when raw materials, which are good for the planet or alternate materials, are adopted at scale,” she added.

India’s Potential to Lead the Sustainable Movement

Fast fashion is a relatively new phenomenon. Shruti highlights how our mothers and grandmothers were slow fashionistas, and the culture of hand-me-down clothing was always prevalent in India. “It's our practices that have changed, with this recent shift in the baseline. We are thinking like this now, but the truth is, we used to consume less and be content,” she said.

According to a report by ResearchAndMarkets.com, the sustainable fashion market in India is expected to grow at a CAGR of 10.6% during 2021-2026.

Bhaavya, from Iro Iro added that India still has its crafts alive, while talking about how India can lead the slow fashion revolution. “If we could leverage our crafts, in a way that could decentralise the economy, that would be helpful,” she said. “One of my missions is to take economic and developmental opportunities to the villages, instead of promoting migration and having people here. So my thought is that crafts could be a driving force in that.”

If we could leverage our crafts, in a way that could decentralise the economy, that would be helpful. Bhaavya Goenka, founder and designer at Iro Iro

Shruti mirrors the thought around craft, as it is handmade, doesn't use heavy machinery, and has far lesser carbon footprint. She elaborates, “A lot of the innovations and good practices around slow fashion are actually coming from craft-based brands. So I see that as our hidden potential, it's a gold mine for us!”

India, with its age-old thriving craft ecosystem, can thus be the leading force when it comes to embracing slow fashion trends. With its myriad traditional weaving techniques and textiles unique to different corners of the country, it can be the hub leading the change.